I’ve had interactions, similar to the one I’m going to describe in this post, with over a dozen of my clients over the years.

My clients will come to me complaining that they have been sued, or threatened with a lawsuit. One of the subjects we must discuss in that interaction is whether there is any insurance available to assist with the defense.

It’s frequently the case that businesses, especially smaller ones where owner/executives are wearing many hats and fulfilling many different responsibilities, don’t have a very precise grasp of what insurance they have. And that’s okay! Part of what I do is read insurance policies to determine if there is a potential for coverage for the problem at hand. So what I wind up doing in situations where the person I’m talking to doesn’t recall exactly all of the insurance policies available is asking to see all the insurance policies that were in effect on the appropriate date. (There’s a bit of an art to determining when that date should be fixed, by the way, but that’s a subject for another day.)

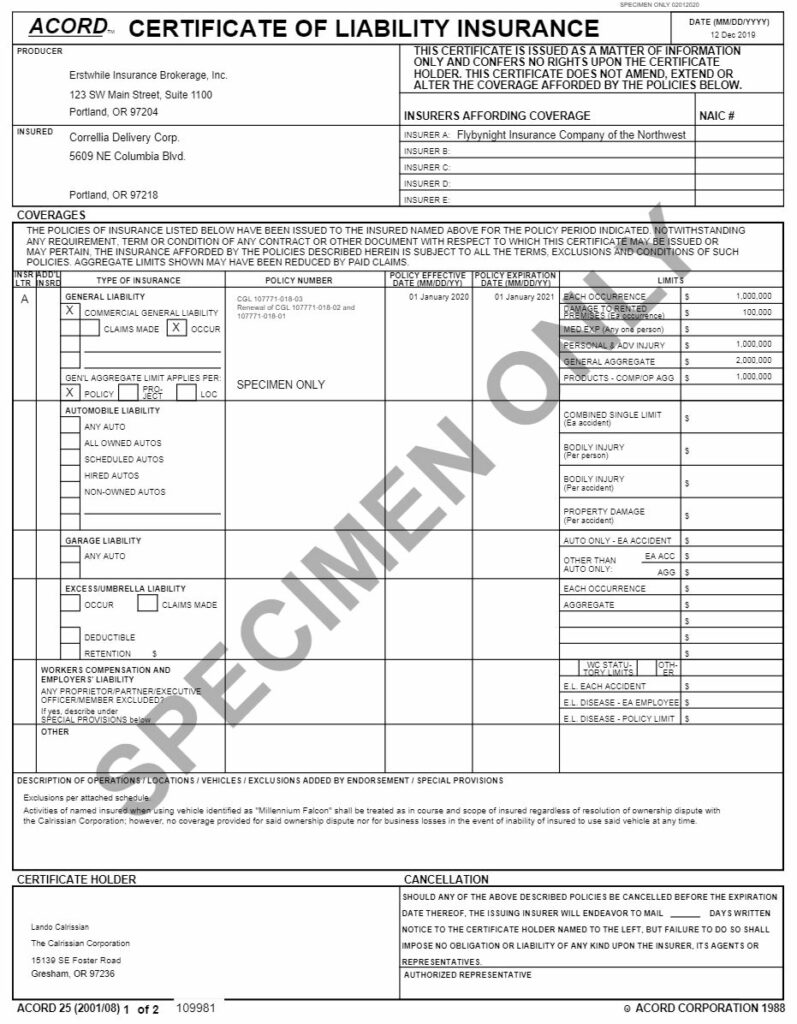

So I’ll ask the client to give me all the insurance policies. Or, if they don’t have them, to get me in touch with their broker. Then, I’ll be given a one-page document that looks something like this:

This is not an insurance policy. This is what’s called a “declarations page.” In this case, it’s a declarations page for a fictional company and a fictional additional insured on a single policy of commercial general liability insurance. But it is not, itself, the insurance policy. The policy is a lengthy, legally complex contract between insured and insurer. The most critical of many important terms is something called an “insuring agreement,” and what’s on this document isn’t it.

Make no mistake: the declarations page is important. It’s part of an insurance policy. It’s evidence that a policy of insurance was issued to the insured named on the declarations page. It tells us in general terms what kind of insurance was issued and what the policy limits are. It may have other information about that policy, such as whether there is a deductible and whether claims and indemnity expenses are taken from a common pool of funding. But it’s not, on its own, a policy of insurance.

It doesn’t tell me what is actually covered. Now, this is a CGL policy, so chances are pretty good that what’s covered is an “occurrence,” which generally means an “accident,” which has a fairly precise meaning developed through years of insurance experience and modifications to variations on the basic general form of this kind of policy, issued to hundreds of thousands of businesses and people by thousands of insurers over the years. But that general understanding of what a CGL policy covers is not a substitute for reading the actual policy.

Particularly endorsements and exclusions, which tend to come at the very end of a policy, and are often custom-written by the insurance company’s underwriters, to limit the scope of coverage in an effort to keep the premium charged on the policy at or near the level requested.

What gets a little scarier is when you realize that the people who generate these policies often don’t read all of the verbiage in them. This sometimes creates a situation where not only does my client not know whether a policy of insurance is available to help resolve a problem, but the broker who wrote that policy doesn’t, either. And the declarations page, which is frequently the only document actually read by anyone who wasn’t the policy’s underwriter, is not particularly helpful to determine whether a given claim is covered or not.

I once handled a lawsuit against a client that I’ll re-name for this story’s purpose “Jones Structural Steel, Inc.” As the name suggests, Jones Structural Steel was in the business of constructing steel structures. The company’s President Ms. Jones came to me with a lawsuit by a plaintiff who alleged that, among other things, the structural steel elements of a carport Jones Structural Steel had built had collapsed on the plaintiff’s vehicle, causing extensive property damage. “Is there insurance?” I asked, which led to the broker e-mailing me the declarations page. As time to respond to the lawsuit was running short, we tendered the claim and began preparing a defense.

The response we got from the insurer was to decline coverage, citing an exclusion that wasn’t even mentioned on the declarations page. Specifically, there was an exclusion from the definition of an “occurrence” for any construction of structural steel performed by the insured! Further inquiry revealed that the underwriter had indeed excluded my client’s core business activity from the scope of coverage on this policy, which meant that it covered not much more than a situation like a customer tripping and falling while visiting Ms. Jones’ office. That, in turn, led to disputes with the insurer and the broker, turning what would have been a relatively simple property damage case into eighteen months of arguments how insurance policies are supposed to be written. Eventually we got it all worked out, but there was no doubt in my mind that Jones Structural Steel had not been well-served.

Not every situation has to be like Ms. Jones’. If you don’t want to wind up in a situation like hers, though, there’s a variety of things you can do.

First, you can and should demand a copy of your insurance policy every time your insurance is issued or renewed. Now that you know the policy consists of more than just the declarations page, you’re better armed to seek out the actual policy.

Second, you should develop an understanding of the kinds of risks you face as a business. That can help you determine if you’ve bought the right kind of insurance and appropriate policy limits to that insurance. Compare your assessment of your risks, in cooperation with your broker, with your coverage profile.

Third, you don’t need to, and probably can’t, address the issue of risks all on your own. Counsel for risk assessment and prevention comes from a lot of places. Some of that is from an attorney like myself. Because my firm focuses on the challenges of employment law, I’m addressing claims that arise under Employment Practices Liability and Directors and Officers insurance policies most frequently. Some of that is from your insurance broker. But also in this arena, your own human resources and occupational safety professionals are valuable sources of information and assessment of what kinds of risks are most prominent, and what can be done to minimize those risks.